A Sense of Being Natural: an Interview with Hannah Adair

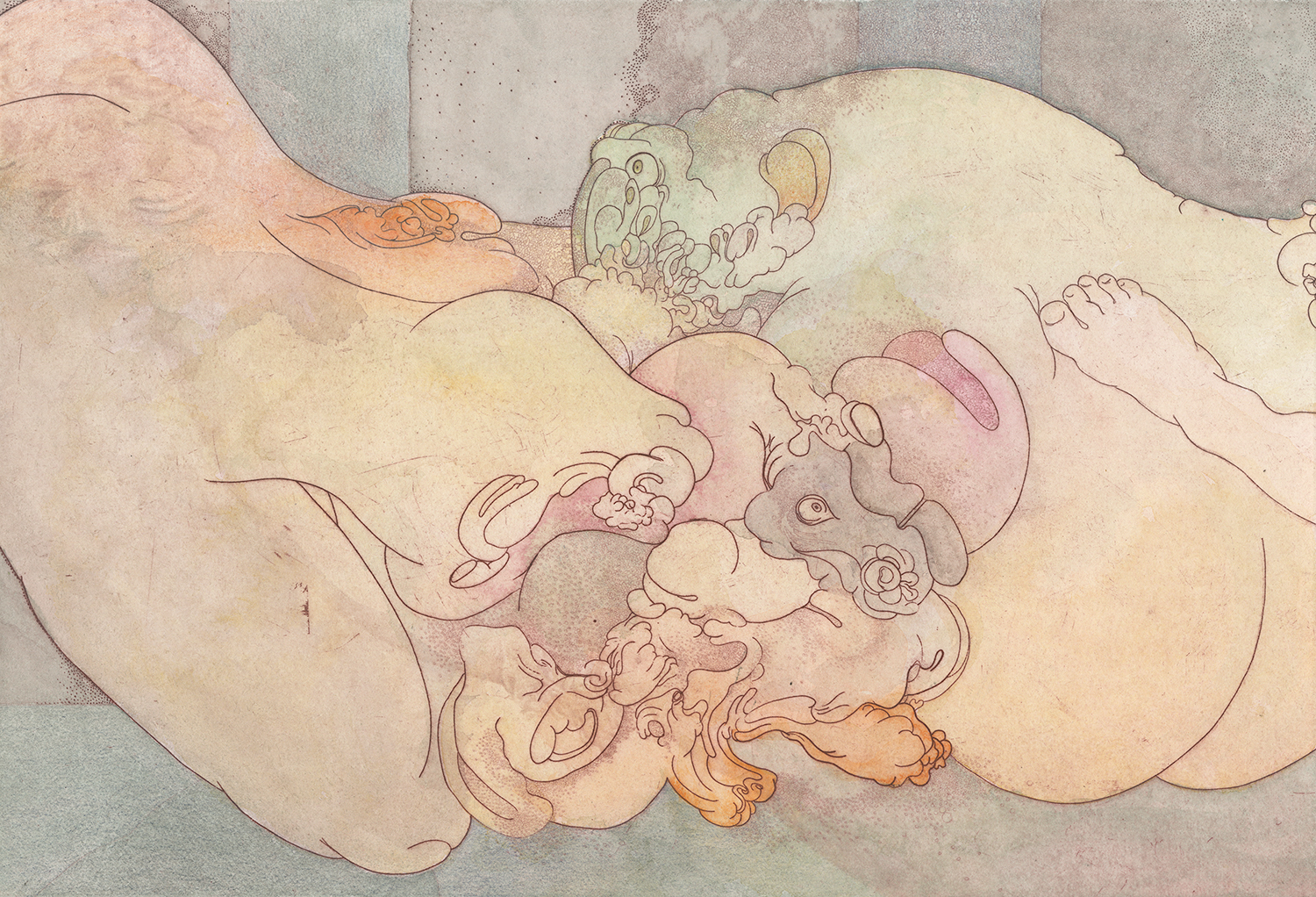

Ever since I first saw Atlanta artist Hannah Adair’s work, I’ve been taken with the muted chaos of her work, which rides the line between cosmic landscape, mythological figure, and abstraction of the psyche as if those things are naturally all the same. It is an experiment in repetition and transformation, as she constantly shifts the meanings of form by reintroducing images in different contexts, always prompting reinterpretation. Adair’s pieces are so comfortable in a place of contradiction, of macrocosm and microcosm, repulsion and attraction, chaos and control, tangibility and intangibility. This work is intricate, demanding such intense study that I highly recommend viewing it in person rather than digitally, if possible--it is art which rewards the viewer for getting to know it, always revealing more about itself. A selection of Hannah Adair’s work is currently on display at Atlanta gallery Kai Lin Art in the exhibition New South III from June 22nd to July 27th.

The following is excerpted from an interview which took place on Wednesday, June 13th, 2018 in Hannah Adair’s studio at SCAD Atlanta.

I’m not making work for somebody else--I’m making work for myself. I like the idea that the meaning of it isn’t fixed--I can really change it from print to print. I can experiment with different color and change the mood of it, change the meaning of it without starting from scratch, like I’m building a relationship with the image.

Siren, 2018. Hannah Adair. Hand-colored etching on handmade paper, 24 x 18 in. Courtesy of Hannah Adair.

It’s interesting--a lot of your work is abstract, or, some of them are abstract, but they are distinctly feminine... It’s kind of like a creation story, but a feminine creation story.

It is 100% about creation. I tend to avoid grids and things like that because it has such a strong tie to masculine painters... And so I think the dot mark, the kind of round, it just has a more organic unit of abstraction and it has such a strong association with time. Women have been being told to make stuff look easy forever. And why should I do that? Like, yeah, maybe it’s labored over, but, it’s not torture. If I get to sit undisturbed for hours and hours and draw and make marks, that’s such a luxury.

There’s a ritual to it.

Yeah, yeah, definitely. Meditativeness and ritual. And it has its own structure that it naturally wants to make. So it’s a way to make choices really slowly. I don’t have to know what the whole thing’s gonna look like--I never do. I wanna be surprised and have some room for chance and to discover what’s gonna happen.

Landscape and figure are constantly recurring. It just seems like there’s so much within that. It’s just, like, humans and environments. What else is there?

[Your pieces] really do seem like you have taken a part of your soul and put it into an object.

That’s the goal. And for me, that takes time. And maybe for some people, if they spent that much time, it would ruin it--they just need to spend thirty seconds and that’s how they “get it”, get what they want out of it. But for me, it really just takes time. It just takes a lot of time. I’m just like, “What is the point of rushing?” I’m not making a product... To me, making something beautiful, that’s subversive. You know?

Well, it’s eternal.

It is! The atemporal universality [movement] is something that women weren’t allowed to participate in when that was going on. I think some people, and maybe this is just my own insecurity, but people dismiss [my work] because it’s neat, clean--on the surface level it can be seductive, it’s pink. I think it can be kind of glanced over as being traditional or boring in that way. But then I think if you do look a little closer, you’d be like, “What’s actually going on in there?”

Lovers Drawing III, 2018. Hannah Adair. Etching and graphite, 10 x 8.5 in. Courtesy of Hannah Adair.

I think, engaging with art… is without a doubt autobiographical. It is what you see in yourself, projected onto what someone else created.

I like to leave it open for that. I’m always interested in what people will see in a work that I didn’t see… When something is abstract or ambiguous in my work, people want to look. Even art students or people who are intellectual or critical, they still want to be like, “What is that? I see blah blah blah.”

In the same way, that’s how tarot cards work. And I love tarot cards! I don’t think they’re gonna tell me my future, but it’s a symbol that you can look at and say, “Hmm… what does that make me think of?” It’s just a mirror to look at.

I kind of think of my works like that sometimes, especially the figurative ones--they have a kind of archetypal thing that makes it less personal. And I can read my own personal thing into it, but I think it leaves it open enough for other people to see something also. And as I build up more, they can have different connotations with each other too.

What prompted the turn to more figurative works?

Figures were there in the beginning... I’m still doing some abstract, like purely abstract works. I think it was an organic process of restricting my practice down to the most simple, one touch, dot dot dot moment, most basic, purely abstract. And then, starting to expand back out from there.

Part of what I love about prints, and papermaking too, is that it’s very visceral and physical. It just feels… normal to have bodies. Because the sensual, tactile element is so important. And, you know, my work being feminine, it’s something I really embrace too. Am I an artist or a woman first? I’m a woman, first.

Lovers Drawing II, 2018. Hannah Adair. Etching, watercolor, and color pencil, 10 x 14.5 in. Courtesy of Hannah Adair.

How would you characterize your own relationship to your body?

You know, mixed, like everyone else. I feel like I’ve gotten to a place where I’m pretty good with what’s going on. It serves me well. It’s been probably eight years since I’ve removed any hair from my body that wasn’t on my head… I think having a sense of being natural is something that’s in my work. The women I draw, they’re round, and curvy, and squishy--which, you know, that reflects my own body image. Making portrayals, I think that’s what almost any artist does. You make what to see, or hear. You try to make what you want to experience. My body is an art-making tool. It carries me around.

[Hair] is a motif I’ve been using more lately. I’ve been putting more eyeballs in there, too. Hair and hairlessness is an art historical thing--it wasn’t considered “timeless” if there was hair, because that was “dirty”. It’s kind of funny, though, because what is more contemporary than hairlessness? I was reading about Manet’s Olympia and how you can’t see any of her hair, but there’s this golden tassel on the pillow that stands in for the hair. Eyeballs and hair. [The use of eyeballs asks] the question of, “How does your body see a situation?” Whether that’s through feeling, in a sensual way, or if you feel the need to turn around. It’s kind of how all of your intelligence isn’t located [in your head]. With drawing, sometimes I feel like my hands are smarter than me--they know what to do, I don’t have a plan.

That ties in with the medium of printmaking, as opposed to painting on a surface, as well. That textural intuitiveness.

I love that there’s a separation between the plate and the print. Even if there’s only one [print], the origin of the image exists somewhere else. The plate, in a way, is its own body, and the print is something that’s projected out from that. And it is physical, there’s pressure. I may have made three sheets of paper with the same pulp and none of them will be the same.

When you pull a print, for metal etching anyway, there’s a metal press bed, and then the plate, wet paper, and then there’s the felt, the blankets. Sometimes the paper has to have a bath. There’s all these funny, kind of domestic words. There’s so much tending and care that has to be done… It really keeps you engaged. A lot of chores.

There’s this association of creativity with femininity and masculinity with technology. But the way you describe printmaking, it’s very domestic, very like craft.

There is a craft association. I feel like it’s abandoned in a certain way, like, there’s a lot of people doing it and the community aspect of it is great, but in The Hierarchy of the Arts, it’s still lowbrow. Painting is still the most valuable. For me, I like that it still has a kind of lowbrow craft association.

But it’s really like a trade, because it has a commercial history. The history of printmaking is so interesting because it’s so varied. Printmaking can be credited with democratizing knowledge, allowing people to read. Before that in the spectrum of history, there’s the oral tradition and the manuscript tradition, and then, print, which dominated from the 1500s until the 70s. That’s a pretty long reign, there’s a lot of stuff in there! And so a lot of it is documentation, sharing information, and then a lot of early prints were reproducing paintings. So, it sort of has this subservient relationship to “fine art” in a way, and commodity. But it also allowed for transferring--in a way it was more democratic and affordable. Like, maybe you couldn’t go see this painting, but you could have a print of it.

It’s interesting how that’s been subverted. Where print once liberated information, with the internet, it’s more [archaic]...

Right! And [my work] now, it’s not even close to mass-producing. It’s reproducible, but not in the same way. Like, what is digital reproduction? It totally changes the conversation. [Printmaking methods] now are totally unnecessary. So it’s liberating--there’s nothing more fun than drawing on a slab of limestone! Any print method, you don’t need it to reproduce--so they’re freed up now for art.