Dusty Pink by Jean-Jacques Schuhl: The Mechanical Ashtray

DUSTY PINK (ROSE POUSSIÈRE) by Jean-Jacques Schuhl. Forthcoming in translation Sept. 2018. $14.95. Semiotext(e). 128 pp.

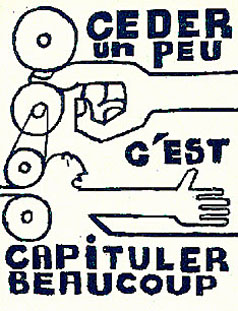

Étienne Decroux, father of corporeal mime, proposed a ban on speech in theatre for 30 years, or until actors are able to use their full range of expressive ability. At that point, noise and speech would be re-introduced gradually and as necessary, not out of laziness and lack of invention. It was the notion of artistic tradition and lack of originality in theatre which he detested, and against which he proposed these ascetic methods. When sound was introduced into the medium of film from the period 1928-1931, there was a “rigorous stuttering” and gestural gratuity which Jean-Jacques Schuhl, observes in his 1972 French novel Dusty Pink (Rose poussière), a text which explores the state of replication and its relationship to the changing world of communication and popular culture. “The only revolution that could have been interesting,” he writes, “would have been a revolution that negated Hollywood while preserving it, overtook.”

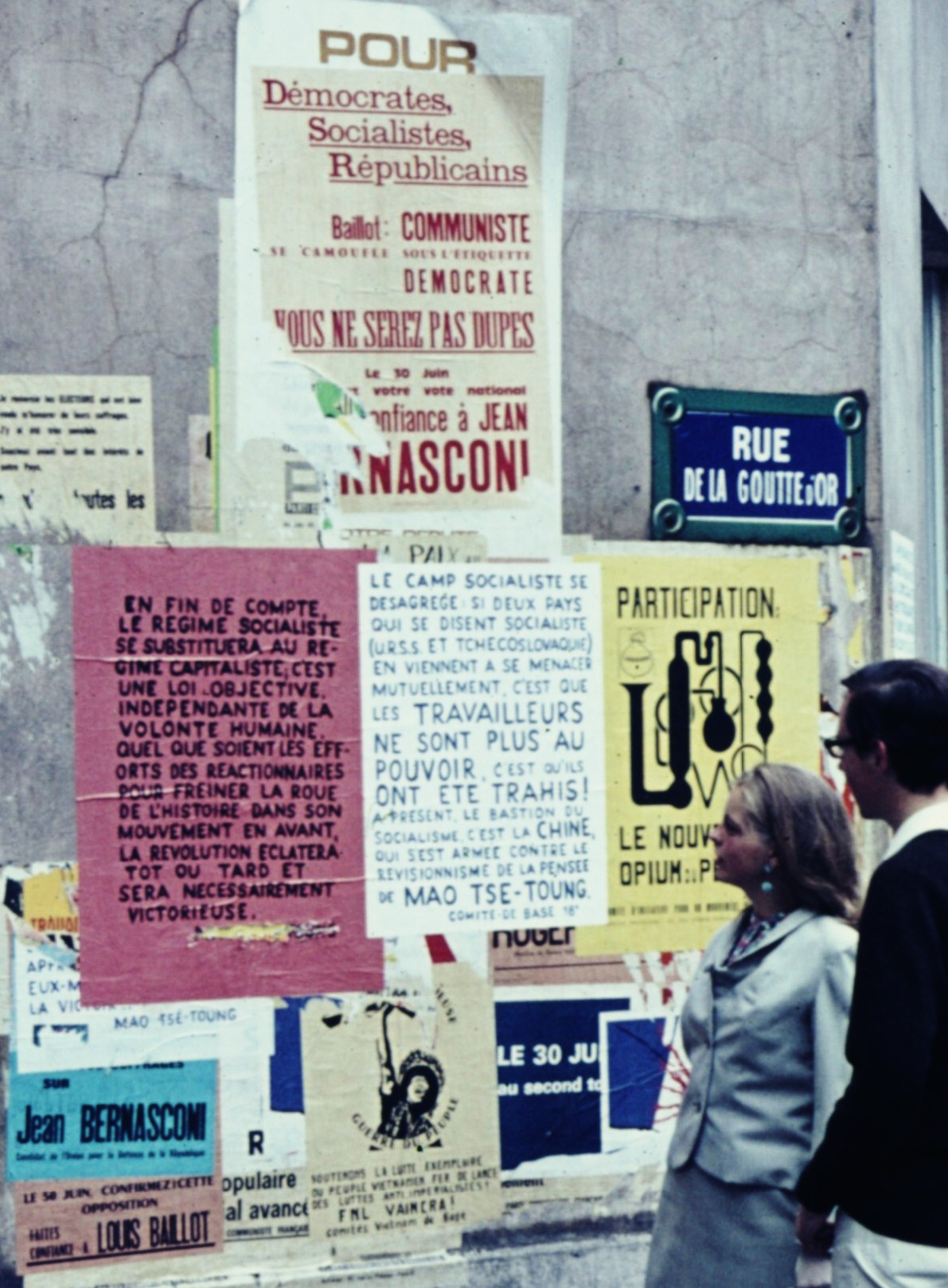

May 1968 by Joan Miró, painted between 1968 and 1973 and inspired by the French protests

Dusty Pink, a forthcoming release in English translation, is a cluttered, chaotic text which meets you only as far as you’re willing to meet it. It can be flipped through with as much attention as scrolling through an instagram feed, to which it will give confused and disjointed impressions which buzz above the cerebral cortex. Or it can be studied and meditated on, to which it will still give confused and disjointed impressions, but along with that, some contemporarily eternal thoughts on simulacra. Taking place in the underbellies of Paris and London from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, among the 1968 French student riots and the Brian Jones-era Rolling Stones, Dusty Pink does not so much live in its time as it fetishizes it and then relishes in its fetish. Cobbled together from magazine excerpts, quippy ads, photographic ekphrasis, dadaist fantasy, and anecdotal observation, it eludes classification (not a necessarily a sign of a great art piece, but a common side-effect of great work). It inhabits the category of fiction as uncomfortably as it inhabits the categories of prose poetry and creative journalism.

French protest, May 1968

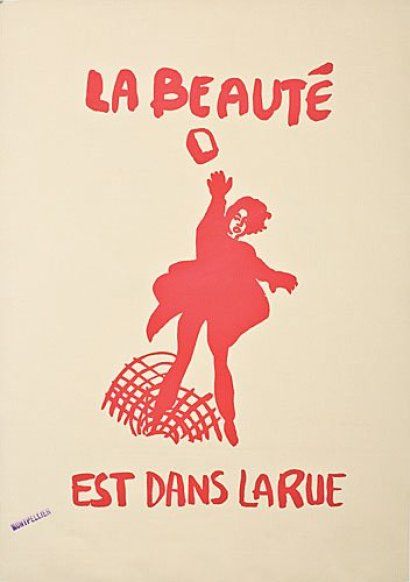

The references in Dusty Pink, which include Marlene Dietrich films and obscure Edgar Allen Poe stories, as well as vernacular images of time and place (France-Soir newspaper clippings, department stores, The Rolling Stones), have almost entirely lost their meaning. They are, at this point, relics through which we can attempt to infer what life was like and how people were. That is, perhaps, too naive--their remaining attributes are the relics which are worn as accessories. The original dies, and its caricature lives in as commodity and performance, through emulation and integration into movements and culture. Marlene Dietrich was alive only in the portions of her which have been referenced and emulated as symbols. That is to say, only in Camp (I, of course, am pulling from Susan Sontag here). She possesses drag queens like a demon. Even though The Rolling Stones are somehow still alive and touring, what makes them real is the cargo shorts worn by suburban dads at the college stadiums they sell out. Mick Jagger now performs drag of his younger self, and it’s deliciously atrocious. There is a point in time when originality is so far gone, it’s hard to fathom it ever existed. In a way, that’s a kind of transcendence.

The whole thing, in fact, is reduced (or uplifted!) to the status of Camp. The text itself, in addressing the world in Camp, has secured its place as a “cult novel”. It too, is Camp. Dusty Pink lets sentimentality run wild, all the while detachedly smoking a cigarette and raising an eyebrow at notions of sentimentality, and considering that the mechanization of the process by which notions achieve cult status is a rather elegant thing. What drew me to Dusty Pink, quite frankly, was a desire to emulate (or perhaps simply obtain) the aestheticism and cool grit of the time Schuhl pokes his scissors into. It’s the same motivation the resulted in the shaving of my eyebrows (to pencil in thin Marlene Dietrich brows for a stage persona), or to buy a basket from Goodwill and use it as handbag (to capture and hold some essence of Jane Birkin). My eyebrows remain shaven, although I have stopped putting forth the effort to pencil in Marlene, and my Jane basket has become something of a decorative piece. Their remaining reference to Marlene and Jane are like visual stutters.

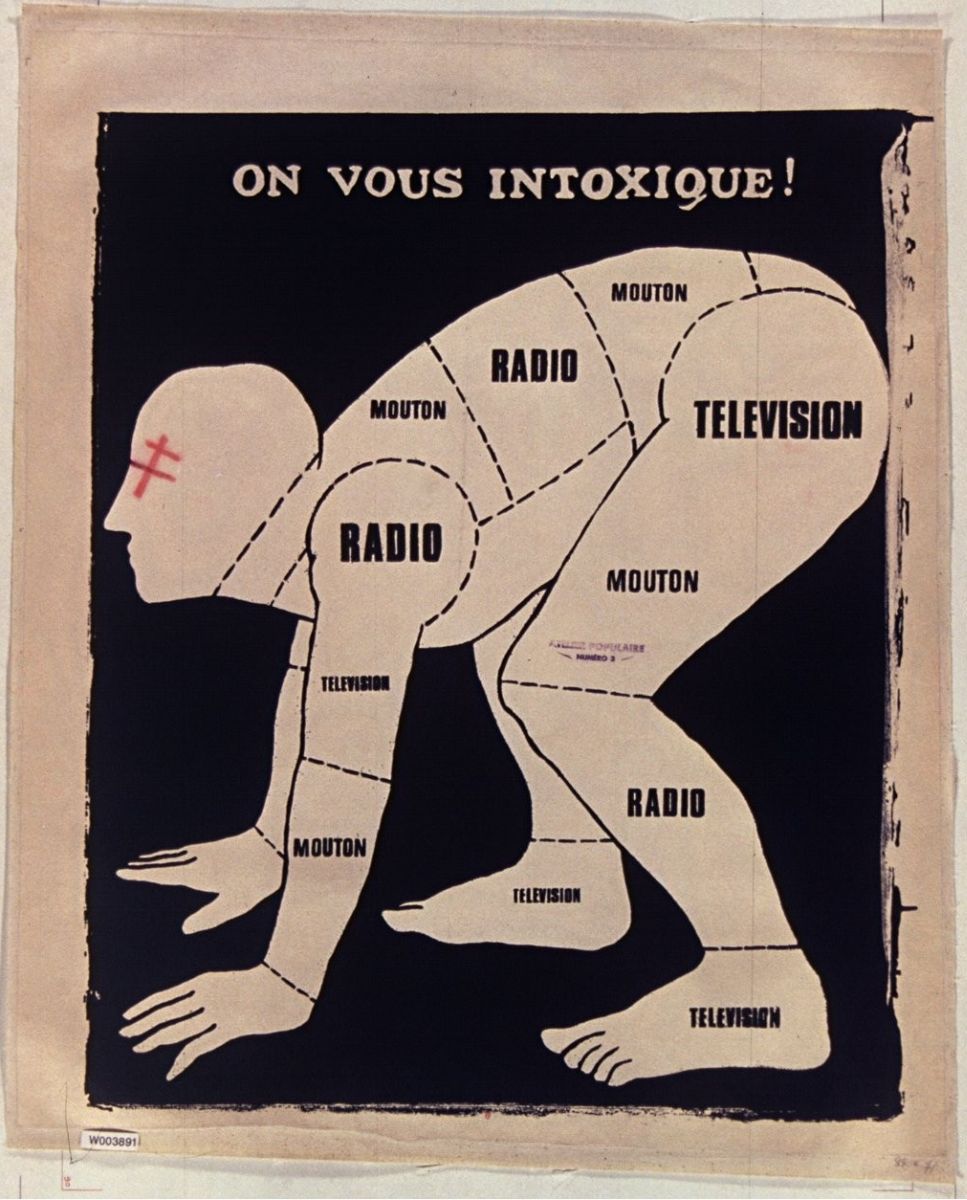

Schuhl lets the electricity and mechanics of modes of communication litter these cities. He builds trash heaps of words so high that those speaking them forget what they’re saying. One can compare the rises of the telephone and television, accompanied by the concept of popular culture, to that of the internet--such shock and revelation Marshall McLuhan once experienced at the dawn of new media. The human attached to the machine becomes another human entirely, Schuhl and McLuhan declare. That’s certain, but a stuttering transitional stage to where we have arrived at now, surely its own transitional stage to a state at which we will shun our outmoded expressions, symbols, and habits. Schuhl’s approach is a kind of laissez-faire parenting, to let it happen, and consider the consequences from afar.

The pillars upon which popular culture rests (and then becomes unraveled) include instantaneous gratification, commodity, and reproduction. Forgive me, the idea of pop culture being so ancient a structure to rely on pillars is likely a messy metaphorical device, as these foundational support members are so structurally intertwined. Additional structural members of the institute of popular culture include counterculture/subculture and authority, concepts which cannot exist outside of each other. Technologies which can generate rapid copies and messages move dialectically--as they contract into forming a cohesive popular image and narrative and give birth to fads, so to do they expand, allowing individuals to curate their exposure. Meaning is transmitted in communication until there is so much information communicated that it is indistinguishable from noise. Whatever narrative formed by conglomeration unravels shortly after the collective setting is established.

The swimming pool at Brian Jones's home, where he drowned

The tools of reproduction and imitation allow for the death of the individual ego (often, though not necessarily, under the illusion of asserting individualism). The ego is lost through assimilation into collective narratives and by adoption of reproduced symbols of the past. Mick Jagger is not the only one whose persona is a disguise (a disguise for what?). The collective and the symbolic totem are comforting, although they are easily stripped--and what remains after the ego, the collective, and historical identifiers have faded away? To Schuhl, little more than mechanical waste, spare parts for recycling. The very countercultural social movements which are birthed in mass communication, and sometimes out of a rejection of it, die as they are proliferated past the extent that they are able to be countercultural. Youth movements are always aging out into middle class, suburban norms. Many a contemporary suburban dad was once a skate punk. Mass communication constantly isolates the present from history, reproducing information always out of context, only holding onto the past subliminally or as an illusion. At this point, mass communication is a machine which neither requires nor services humans, only itself. Humans are left to acclimate to this new disenfranchised state.

French loungewear ad, circa 1966

Schuhl says it’s a kind of evolution, and in some respects, finds it elegant. That we are left with purposeless tics, vestigial organs, alien to our own bodies. In what way he finds this beautiful is hard for me to say--whether because it is glamorous or essential. That we make beauty products from war, make a cat eye from the ash of civilization. That Vogue may market our undoing as a chic must-have. It may even market its rejection of markets. Anything organic about us is boiled down to the synthetic, and then sold as organic. [An excerpt from yesterday’s online Vogue: On top of a 45-minute sleep session, they offered Sleepy Jones pj’s (not to keep), Sunday Riley beauty products (those you can take home), eye masks, earplugs, and a toothbrush and paste (you can have those, too)—and all for $25. In the current wellness world of $11 juices made of kale and chlorophyll and a price tag of $85 to freeze your entire body for three minutes, that’s a steal.]

Though it is, to me, such a clumsy, careless thing to be undone by the doing. If simplicity is elegance, I concede--how simple and inevitable for us to have ended up here!

Katherine Beaman